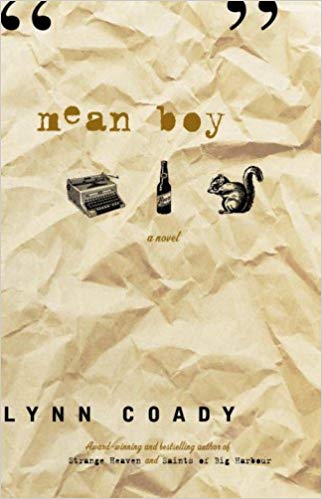

With her third novel, Mean Boy, Lynn Coady takes several risks which leave the reader wondering: is this just another solidly crafted book? or might it qualify as something more substantial? My ambivalence on this point stems from the nature of the risks she takes. The first risk is the novel’s subject matter—poetry. Coady tells the story of a young man, Lawrence (Larry) Campbell, from rural Prince Edward Island working class roots, who aspires to be a poet and so crosses the Northumberland Strait to attend a small mainland university, drawn there by the Big Name Poet, Jim Arsenault. We sit in on poetry workshops and readings where students evaluate one another’s work, sometimes nasty, sometimes clueless, most often hungover. Is the poetry banal? Is it pretentious? Could it hold the kernel of an emerging talent? Who’s to say? How can anyone really be sure? Just as the students engage in back stabbing and petty jealousies, so too their mentors. Rural Jim Arsenault bears a long-standing grudge against urban Derrick Schofield and this rivalry has worked its way into nasty reviews of one another’s work. Do the reviews contain any legitimate observations? Or do they merely reflect the clash of strong personalities? In the end, all this writing about writing acts as a tacit invitation for the reader to scrutinize Coady’s work in the same way. Is the novel banal? Is it pretentious? Could it hold the kernel of an emerging talent? At the very least, one must say of Coady that she has confidence when she openly invites such scrutiny.

The second of Coady’s risks is her decision to tell the story from the point of view of a young man. It is always a challenge to write a character of the opposite gender. The novel offers many reasons for a female telling. Set in 1975, there are hints of tension between feminist murmurings on campus and the patriarchal world view that dominates the university’s rural setting. There is the older cousin, Janet, a senior on the same campus who spends all her time with a cabal of feminists and eventually announces that she is pregnant. And lurking in the background, but no less eccentric than their husbands, are the wives of the poets and the academics. Still, Coady chooses to follow Larry through his initiation into the life of the poet. He has a thing (only in his mind) for the waitress at the local diner, and he gets a hard on when he sits near the secretary to the head of the English Department — convincing stuff for a writer who has never had one personally.

The third risk is Coady’s decision to write an unabashedly Canadian novel. Even the title is unabashedly Canadian—an allusion to a poem by Milton Acorn who, like the novel’s narrator, was born in Prince Edward Island. But it has been a long-standing tradition among Canadian writers to be deliberately vague about setting and place names. Perhaps this tradition was dictated by economic necessity—if you wanted to sell books, then you had to appeal to a British or to an American audience. I remember how I smirked when I first read the title of Hugh Garner’s detective novel, Death in Don Mills. Don Mills is a rather dull suburb of Toronto, and to those of us who live nearby, it seems inconceivable that anything remotely interesting could happen in Don Mills. Why not be a good Canadian writer like Mavis Gallant and move to Paris? Why not be like Margaret Atwood and invent futuristic settings? Or be like Michael Ondaatje and write about Hungarian counts who dig excavations in the Sahara? What was Coady thinking when she decided to write about a teenager from Summerside, PEI who attends a small university in New Brunswick?

And yet, Coady’s approach is wholly appropriate to one of the novel’s principal themes: talent lurks in unexpected places. A person who is sophisticated, well-educated and urbane, may never have been blessed. The Muses are capricious when deciding upon whom to bestow their graces. A boy from Summerside may well be the next Big Name Poet. And, by implication, the next Big Name Novelist is as likely to come from Cape Breton as from anywhere else. We see this theme played out in many different ways. Larry tries to “psych out” his mentor, “the greatest living poet,” and discovers that Jim Arsenault is a needy, manipulative, alcoholic married to a woman who doesn’t fit properly into any of her clothes, smokes like a chimney, and tells all the poets to fuck off. Janet, the hick cousin who gets knocked up, turns out to have staged the whole thing so that she could observe her family’s reaction. The result is a published paper and admission to a graduate program at Columbia—hardly what Larry would have predicted for the girl’s future. And then there is Charles Slaughter, the three hundred pound football player who, inexplicably, loves to hang with poets yet gives them all noogies and passes most of his time in states of altered consciousness. It is to Slaughter that Coady gives the final word, a poem of his own, banged out on Larry’s typewriter while somewhat intoxicated. Is it any good? Who’s to say?

The last word: Coady’s Cape Breton roots figure large in this novel. Above all, Mean Boy is about storytelling, the way you might expect to hear it told down east around a dinner table. It is driven by characters, big as life, with a lilt in their voice and a drink in their hand.